The Issue

The issue with translations unfortunately is a difficult question because it is not just a matter of which translations are easier to read, or more beautifully crafted; but it also very much involves the issue of which translations are most faithful to the Scriptures that God immediately inspired. Most often, this discussion is argued in terms of formal equivalence and dynamic equivalence. That is, should translator’s focus more on word-for-word translations or should they focus more on communicating the ideas of the text? As a kid, that was the main part of the discussion that I knew, and I had my opinions of it and that’s why I read the ESV. However, during college, I took a little deeper dive into a completely different part of the discussion, that being the issue of textual traditions and what is called textual criticism.

A Little Story

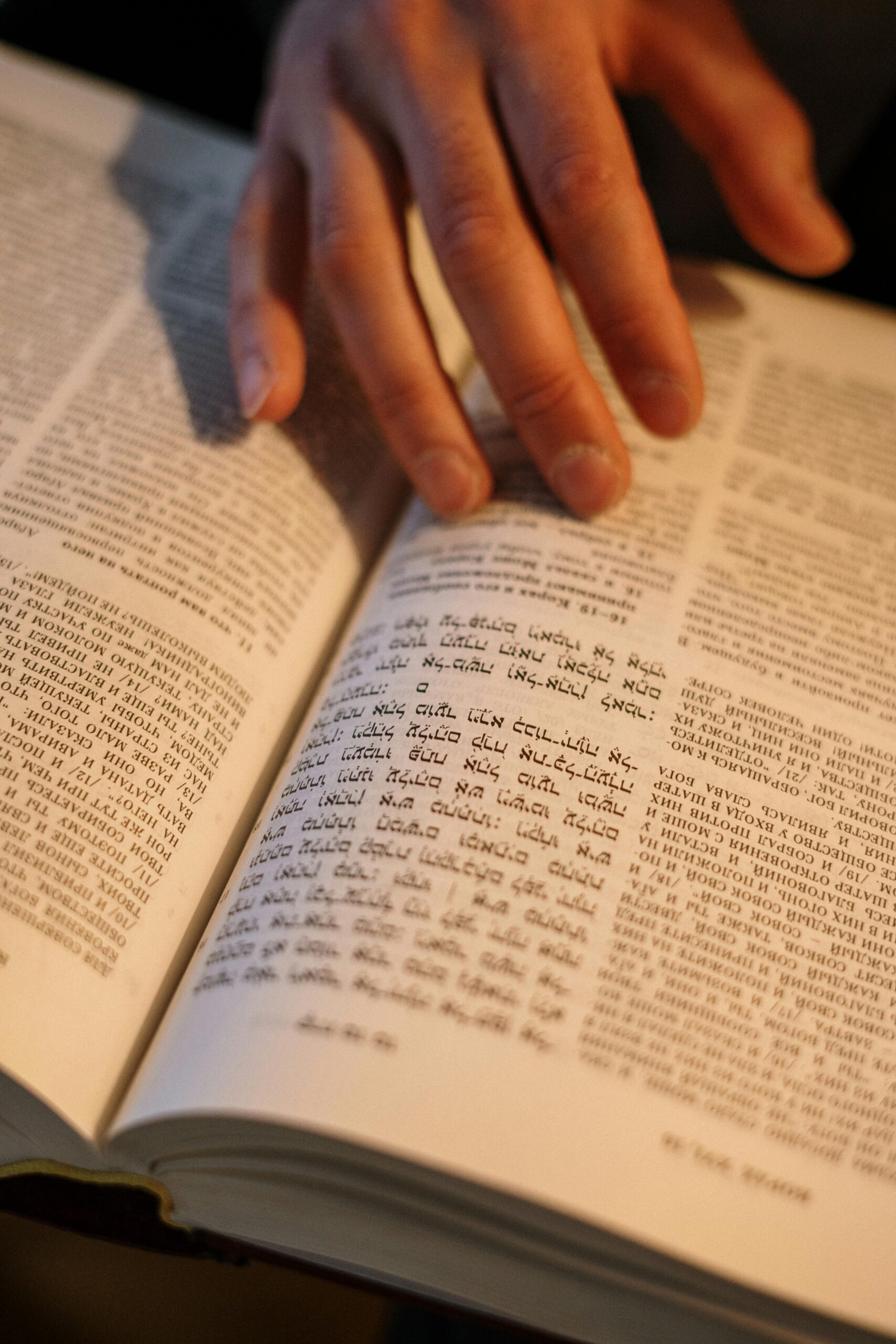

I learned about the various manuscripts (mainly Greek), how they differed from each other and how scholars have shifted their views on what they treat as the most reliably copied texts. Since I can have a pretty-strong geek streak, I ate it up. Not everyone likes textual criticism, but I did. For those of you who aren’t familiar with it, the modern compositions of our Greek New Testaments are loaded with symbols (like footnotes) which differentiate between the various manuscripts and what they say…and there are a lot of them. The bottom of every page of the New Testament is littered with them and a curious person could spend a lot of time trying to figure out which read is the right one.

But that was just it. How could I really be sure which one was right? I remember when I began to study particular texts from the New Testament, when I found a textual variant (a place where the manuscripts differ), I looked at those “footnote” and after a little while thinking, “Man, I don’t know! I’m not going to spend a ton of time trying to solve it, I’m going to keep working on my sermon/lesson, so I guess I’ll to let it be.” Similarly, I remember reading my Bible in my devotions, finding certain, wonderful observations in my ESV and feeling an immediate sense of deflation because I had feeling there would be a variant somewhere in that verse and I wasn’t sure of my findings any more. Which variants were right? Who really knows?

Telephone

Nevertheless, I just had to hang on to this framework of using these variants because, quite frankly, it was and is the scholastically accepted way AND it on the face of it, it is a very logical framework.

In a nut shell, the use of textual criticism is method of trying to sort through the bad copies of the Bible in order to find those ones which are most accurate. Basically, it is a method to attempt to “reconstruct” or “purify” our copies of the Scriptures, word by word. This “recomposition” is conducted using various criteria (where the manuscript was written, how old it is, whether the readings are longer, shorter, easier or harder, etc.) and the idea is that the older a manuscript is, the closer in time it is to when the original book was written and therefore more likely to be accurate. Imagine a game of telephone. The guy at the end of the chain is going to be far more likely to change/“corrupt” the original phrase than compared to the second person in line. And at its simplest, this method of Bible reconstruction is trying to find the guy who is second in line to Paul, Peter, Mark, etc. Most modern Bible uses the text that is composed of this idea, called the critical text. The ESV, NASB, NIV, Holman, are just some of the more famous ones. But the idea just made sense to my mind. And, in all actuality, when I was instructed on textual criticism, I was never presented with a good alternative position. The other ideas were honestly presented as archaic. Plus, every sermon I heard which even touched on the subject, I heard a trusted pastors say, “The oldest and best manuscripts say…” and I believed them. But this brings me to my ultimate question and the point of this paper: why did I believe them? How did they know those texts were the oldest and “best”? Do you believe them? Why do you believe them? How did you choose your Bible translation?

A Few Points that Helped Me

I would simply like to offer a couple of thoughts that led me to change my mind on this subject and what I’m asking from you is a chance to hear me out. My dad and mom were actually the people who began to poke at my scholastic learning to try to help me see this textual issue from another way. And for me, the entire argument boiled down to theology and history.

Remember, the entire premise of my framework was that the scholars have to rebuild the Bible. Yes, we already have very close approximations of the actual, but we still aren’t there and that is why the scholarly Bible societies are still producing New Greek texts. Currently, we have the Nestle Aland 29th edition in publication and no one knows which edition will be the last. But that is part of the point. These scholars have no reason to stop publishing new editions because there are always editions to make to ever “purify” the texts of our Bibles. To use our illustration of telephone, we have yet to find the Bible owned by the man whose was second in line to the apostles.

Preservation and Textual Criticism

Now, I did not see it when I first learned textual criticism, but this position is based on a huge theological assumption, that being that God only mostly preserves His Word through history and leaves the rest up to man to reconstruct it. You see, historically, Christians over the centuries actually discussed manuscript variants, but there was a general consensus as to how the Bible should read until the 1800’s when new pursuits of two famous scholars (Wescott and Hort) led to new questions and new and different copies of the Greek New Testament. The honest person who holds to this reconstruction view of the Bible has to admit that he believes God has not fully preserved His Word for His church’s use through all ages. Now, I remember, I was on a flight once and a Muslim couple told me that they believed that the Bible had been corrupted, to which I responded, “Do you think God would let His book be corrupted?” Ironically, I was holding to this very same textual critical position at the time. I should have heeded my own question. Do I think that God would let His book be corrupted? I missed it then, but now I simply cannot believe that God would do that because of what the Bible teaches. The Bible teaches that God keeps, guards and protects His Bible from errors that might sneak in. The Bible teaches that the Scriptures are God’s “pure” words (Ps 12:6) which He Himself said could not be broken (Jn 10:35), nor could a “jot or tittle” pass from the Law until all is fulfilled (Mt 5:18) and that, “Forever, O LORD, Thy Word is settled in heaven” (Ps 119:89). The idea here is that God cares for the eternal purity of His Word and has taken measures to see to its preservation for all generations. In fact, this is the confession of the historical, Protestant denominations, “The Old Testament in Hebrew … and the New Testament in Greek … being immediately inspired by God, and, by his singular care and providence, kept pure in all ages, are therefore authentical…” (Westminster Confession of Faith 1.8; emphasis added, copied 2/10/25 from http://thewestminsterstandards.com/wcf-chapter-1-of-the-holy-scripture-1-8-1-10/). To put the fail nail in the coffin of this problem, the current science of textual criticism now believes we will never be able to recreate a one-hundred percent Bible. That is a big problem that proponents of this position have both to admit and to wrestle with.

The Sheep and the Shepherd

Therefore, the alternative position to which I now hold is known as the Received Text position/Confessional Text position. There are only a handful of English Bible translations based on these Greek manuscripts, but they are famous, and in some cased now, infamous. They include the King James Version (otherwise known as the Authorized Version), the New King James Version and the Geneva Bible. The idea behind this position is that instead of trying to reconstruct the Bible, we just read what God has “kept pure in all ages” and which the church has organically recognized to be the Scriptures in what is known as the Textus Receptus. The emphasis here is that the church recognizes the authentic copies of the Scriptures, not by how old the paper and ink are, but by whether the church has heard the voice of the Shepherd in them of not. The Lord Jesus said, “My sheep hear my voice” (Jn 10:27). This verse summarizes our position. And as the Scriptures have been copied, in organic fashion the church has recognized what are the authentic words of Christ and have left behind those copies that are not. That is why we see it as such a big deal when all at once, in the 1800’s, the certainty of our Bible was questioned. Did Christ really let His church miss His voice for 1800 years?

What About the Old, Old Manuscripts?

But, there are some of you who likely know something of the details of this topic, and you are pressing in on the age issue again. Vaticanus and Sinaiticus are really old manuscripts and they differ significantly from the Textus Receptus, the oldest representations of which are something like 400–700 years newer than Vaticanus and Sinaiticus. That is a good and very fair question, one which held significant weight with me. Here are two responses for your consideration.

Even in the most ancient times of the church, heretics were actively corrupting the copies of the Scriptures. Marcion, for example, was at least a partial contemporary of the apostles, and on at least one occasion, he was called the “Pontic mouse” which “gnawed the Gospel to pieces” (Tertullian of Carthage, quoted by Dr. Jeff Riddle; accessed 2/10/25 from https://www.trinityfoundation.org/journal.php?id=380). What that means is this: If you were to find Marcion’s New Testament in some library in Syria, it would be old, very very old — even older than Vaticanus or Sinaiticus. But age doesn’t determine whether Marcion’s was a good copy of the Bible or not. In fact, I would go further to say that the best determination to know whether it was a good copy was if other Christians heard the voice of the Shepherd in it and began to base their copies on his.

Is Newer Necessarily Less Reliable?

Second, consider an illustration of two articles of clothing. My mother is a great gift-giver and one of the things she gives me is clothes. In my drawers, I have found t-shirts that still have tags that may have been in there awhile; and in the same drawer I have t-shirts that are all painted over and have holes and frays on them. Do you know which shirts I wear more? Can you guess why I wear them more? And do you know which shirts wear-out quicker? The point I’m making is that just because I have an old t-shirt in the drawer does not mean I like to wear it. In fact, the shirts I’ve gotten the most use out of are totally worn out and gone. So yes, it is true that the oldest, Greek copies which roughly represent the Textus Receptus are comparatively new, but I submit that it is logical that the copies which the church got the most use out of would have to be newer since the older copies wore away.

Conclusion

Ultimately, here is what it boils down to, I argue that instead of asking simply how old a text is, we should ask what is the text the church has trusted over the centuries. In essence, what is the Bible that Christians continued to read when the “New Marcionic Translation” hit the press? That is the Bible I want to read.

So to sum it all up, the issue of Bible translations is not just about which writing style we like or which translation has the most beautiful pictures or phrasing, or even just about literal vs. less-literal translations. The question of which manuscripts also comes into the mix. If I haven’t been able to persuade you to my position, I hope at least that I’ve been able to give you something to think and pray about. And I encourage you to do that. Search the Scriptures and pray about what the Bible has to say about the doctrine of its preservation.

If you are interested in this topic, reach out to me on FaceBook or if you have my number, shoot me a text. Until then, I’ll just leave you with my question: How did you choose your Bible translation?